You’d think someone who suffers fatigue would sleep like a baby, often and long. It is not so.

The cruel irony of ME/CFS is that sleep is as hard to come by, and as unpredictable, as love or fortune. Sleep can come easily by ten p.m. one night and hold off until three a.m. the next. It can hit at one in the afternoon, like a sudden, unforecasted snowstorm, last for five hours, and then stay away until dawn the next day. If it settles in at a normal time in the evening, it might very well stick around for the entire next day, while most folks are putting in a full day’s work.

Most of the time, sleep hangs around way too long in the morning, sometimes until noon. And then every so often, for no reason at all, it departs at daybreak and gives me what I almost never get: the hope of the rising sun and a full day of wakefulness.

Sleep is like the poor rabid dog in Old Yeller, zigzagging down the street at the end of the story with no control over its movements. Sometimes, I just want to shoot it.

As I understand it, sleep is like this for most people with ME/CFS. I’m not sure anyone truly understands why. (If you have an explanation, please share!) I believe one theory is that our autonomic nervous systems are awry, so the things our bodies would normally do without thought—sleep, digest, fight infections—they don’t do very well.

Of course, many older adults struggle with sleep. Such struggles are not uncommon. When I’m up in the night, even as late as two or three, I can see the light on over at my retired neighbors’. And I know my husband often wakes long before his six o’clock alarm, wishing his sleep had lasted longer. Nevertheless, I have the sense that, for the most part, adults my age are heading to bed some hours after the sun has set and are waking around the time the sun is rising, give or take. Whatever difficulties they may have with sleep occur within a basic regularity of sleep and wake cycles.

The only way to capture the difference between “normal” sleep and ME/CFS sleep is to picture it, so I created two charts.

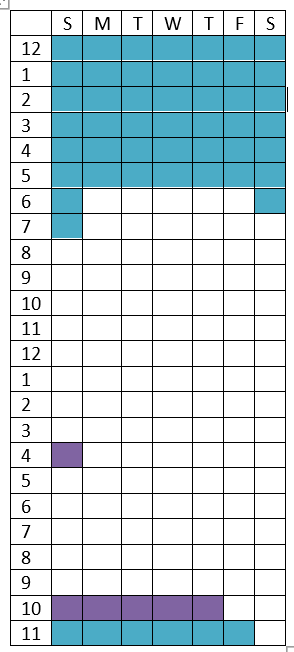

The first is a chart of the hours I imagine a healthy adult sleeps and rests. Sleep is shown in blue, rest in purple. This adult gets into bed around ten on weeknights, reads for a while, and then falls asleep. On Friday and Saturday nights, she watches TV and skips reading. Watching TV that late may very well keep her awake, so she sleeps in a bit on Saturdays and Sundays and sometimes enjoys a rest on Sunday afternoons.

Normal Adult Sleep and Rest Chart

This is, of course, an imagined average, from which actual adults surely vary widely. My sisters, for example, are in bed by nine and up well before six every day, including weekends, and I doubt they’re getting a nap on Sundays. Some of my friends are night owls; they’re awake after midnight, productively engaged, and then rise later in the morning. The key, though, is that their patterns are fairly regular.

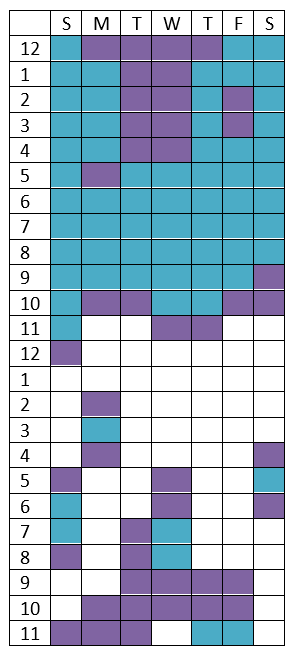

Now my own chart. Again, sleep in blue, rest in purple. And rest does really mean rest: lying in bed listening to music or a podcast or doing nothing. Watching TV and reading do not count as genuine rest for people with ME/CFS.

ME/CFS Sleep and Rest Chart

The most notable feature of my chart is the far fewer white squares. This is what I mean when I tell people (the few I do tell) that I have a limited supply of “energy dollars” to spend each day.

Having few energy dollars means that I will miss out on things and not accomplish much. But the really awful part of sleeping like this is the embarrassment.

One day last summer our ninety-year-old neighbor knocked on our back door shortly after eleven. I felt I had to answer because he might be in need of something, but I was in my pajamas and bathrobe. When I opened the door and he saw me, an awkward chortle escaped him. He looked down at the floor. I could only guess what he was thinking: Why is my neighbor in her night clothes in the middle of the day? My cheeks burned. (I haven’t explained my illness to this neighbor, nor to many others.)

To sleep in the middle of the day, when other adults are working, contributing to society, socializing, and just generally being adults, is to land in the realm of childhood—naps, and pjs, and lines on my face from the pillow at two in the afternoon. It’s not answering texts and not replying to emails and not picking up the phone. It’s eating a peanut butter sandwich for dinner because I wasn’t awake to prepare a meal. It’s incompetence squared.

When family or friends ask me what I was “up to” today, I never mention the hours of sleep and rest. “Oh, I haven’t been too busy,” is my evasive reply. I can’t imagine that there is anything to be gained by telling them I just woke up and am still in my pajamas.

And so the invisibility of ME/CFS continues. I perpetuate it by not being honest about the contours of my daily life.

Consider this my confession.